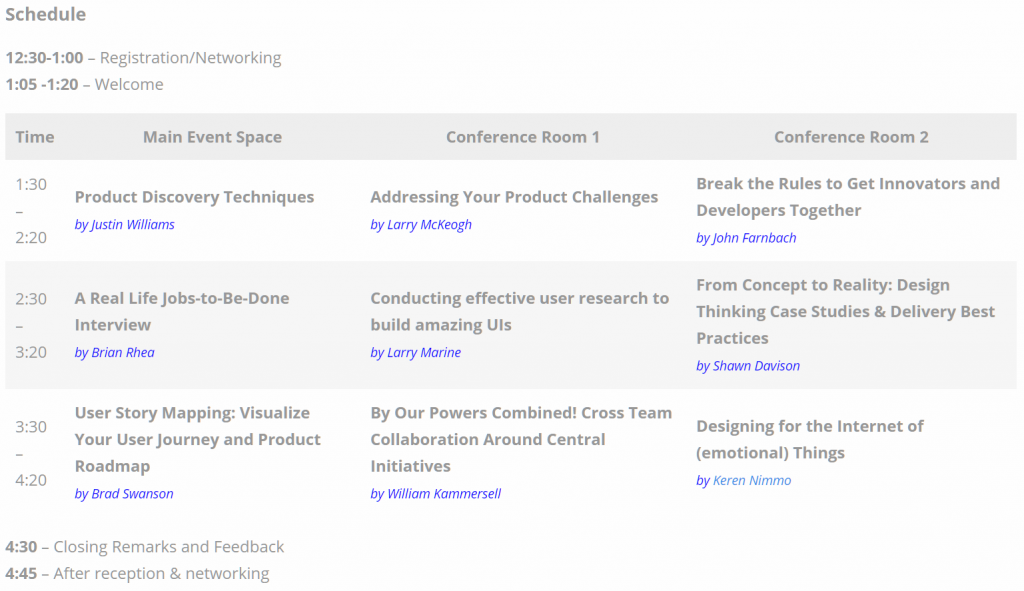

A few of the product managers from Travelport and Pearson took a Friday afternoon off to join in the Rocky Mountain Product Camp in downtown Denver. Participants had the opportunity to choose several sessions from design thinking, to sourcing customer feedback, to process and collaboration between developers and marketers. We voted on the sessions to offer in advance, which collapsed in to 3 session time-slots with 3 offerings per slot to choose between. Here’s the schedule:

The first session I chose was presented by John Farnbach – “Break the Rules to Get Innovators and Developers Together.” It started with a case study on The Royal Dutch Watch Company in 1674, where Chris Huygens had an idea that would revolutionize the time-keeping industry by transforming large clock/pendulum technology in to a mobile form-factor that people could take with them. Chris has a prototype that works, but it’s rough and still too large.

What are the next steps? How does the developer/engineer figure out what use case and customer segment to focus on and what to build? How to the marketers and business people figure out what the customers want and are they willing to pay? Somehow, working from both ends, these two groups must meet in the middle.

Inventors look at innovation, opportunity, reputation and developers look at schedules, budget, and business case. In the middle are delay, waste, and risk that come from technical challenges, changing requirements, new applications, unknown customer segments, etc.

There are best-practices like the Phase-Gate process which is a waterfall methodology – requirements are frozen once you’ve passed in to the design phase. However, the problem is that once you’ve frozen the requirements and gotten to the end and are ready to launch, you have no flexibility to refine or alter what gets built based on new information from the market or from your engineering team. One of the biggest barrier between an inventor and a developer is therefore frozen requirements.

In agile software development, you do minimal upfront planning, set specs on the run, do continuous learning, and get fast feedback in 2 week increments. However, with hardware, you have to do something a little different. You still recognize you don’t know the requirement when you start and identify uncertainties. Then you build experiments to test and accelerate learn about the uncertainties.

Starting with flexible requirements, you should be thinking about a value proposition, not technical specs. Focus on customer needs, not solutions. Then identify the project constraints like financial, schedule and resources.

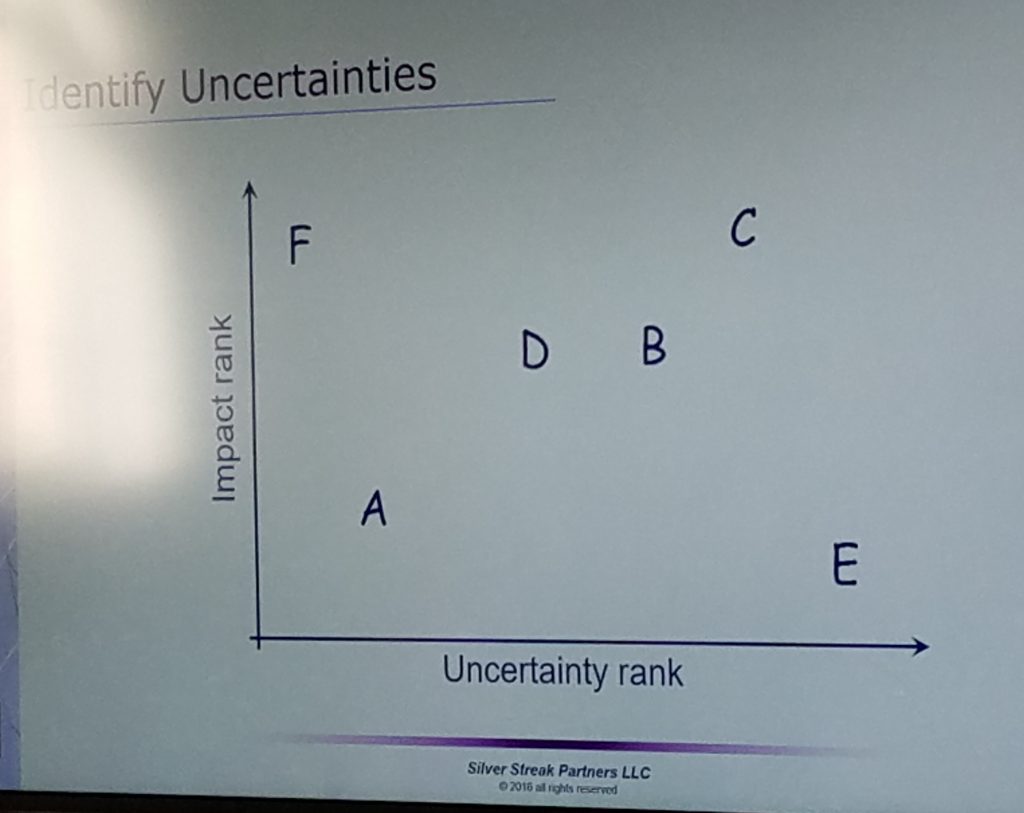

You need to think about your segmentation/value parameters to suss out the requirements trade-space. In this example, we would be thinking about things like accuracy, price, size, manufacturing costs, and mean time between servicing. Once you’ve identified these uncertainties, you can build a graph with Impact Rank on the Y axis and Uncertainty Rank on the X axis and inform your decision on which one to tackle first. In our example, the participants in the room voted that mean time between servicing is the most uncertain and hardest thing to simulate/test. But, it might not be the highest on the impact scale.

It’s all about accelerating learning and feedback to plan design cycles. This includes speculation, which would be your next design cycle. It also includes exploration which is time-boxed, focused, and expedient. Finally it includes adaptation, where we have open questions that explore business impact that lead to refinement of requirements. The cycle of speculate, explore, and adapt continue until all questions are answered. As you are cycling, you keep uncertain decisions open and close then when you know more and you can.

So, in the end, you want to design for flexibility to break down the barriers between the business and the engineering team.